|

Native American Redwood Ecology

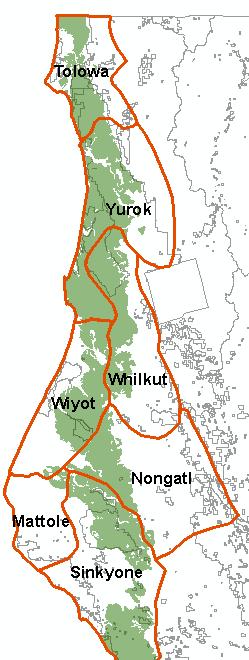

No fewer than twelve recognized Native American groups lived within California's redwood forest prior to 1850, and seven of these occurred within the northern redwood forest (right).

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Tolowa, Whilkut, Nongatl, Mattole and Sinkyone were Athabascan groups that had arrived within the last millennium. The Yurok and Wiyot had arrived a few centuries earlier and had either displaced or merged with a pre-existing people that had lived in the area for thousands of years longer.

The only substantial mechanism that these people had to modify vegetation over large areas was fire, and ethnographic research reveals that every tribe used fire for wide ranging purposes.

Tanoak acorns were a primary food stuff for most coastal tribes, and some are known to have secured individual tanoak for generations. They maintained these groves and improved the quality of the annual acorn harvest with fire. Frequent low severity fire nurtured the development of large trees that could easily be killed by severe fire that resulted from excess fuel accumulation. Burning also reduced the weevil population to reduce loss before and during storage.

The landscape implications of these fires is difficult to know with certainty, but a far larger area could have been burned to improve hunting. Broadcast burning of the forest increased the quantity of food for deer and other game and it made hunting itself far easier. Prairies and brush areas were regularly burned to improve game habitat, to nurture grass seed for food, to scorch grasshoppers for food, and to generate fresh materials for basket making. |

|

|

Several tribes used redwood trees for building materials. The Tolowa and Yurok, in particular, were known for their lodges made of redwood slabs and bark. Redwood logs made excellent canoes, and coastal tribes traded redwood canoes with interior tribes for goods.

Scattered accounts of Indians who lived in redwood cavities may reflect a common if only seasonal custom. Early in the 20th century one of the few surviving Lolangkok Sinkyone stated that he was born in a redwood hollow in Humboldt Redwoods State Park, where his family spent the winter. Other families lived in fire cavities in Redwood National Park as recently as the late 19th century.

A long-standing debate has been the extent of Native fire influence on the landscape as a whole. Fires were not ignited everywhere, and fire spread may have been limited by fuel continuity and moisture in humid ecosystems, such as the northern coast redwood forest. Human ignitions may have only had a local effect. |

Across the interior West, extensive fires of the past occurred during droughts and while fuel was important, fire frequency was limited by climate variability. Ignitions in these dryer sites were not limiting as they appear to be along the redwood coast, but the importance of climate and fuel continuity on fire regimes in the coast redwood forest can not be discounted. The relative importance of human over fuel and climate factors is likely to increase toward the coast and near their village and resource procurement sites. This pattern is somewhat suggested by differences in historical fire frequency across the north coast.

In recent decades, Redwood National and State Park managers have restored fire in upland prairies in part to provide tribal members with the traditional materials used in basketry and to check the encroachment of Douglas fir. However, the value of adopting a historically-based burning model in residual old growth and second growth is a more difficult question. Fire in redwood can be difficult to control and has both desirable and undesirable consequences--both of which can last for decades to centuries. From the dryer forests of Del Norte County in the north to the southernmost extent of redwood, a modified Native American burning model could easily provide long-term benefit for sustaining and restoring certain desirable forest attributes, particularly in those stands that are at high risk of wildfire. In the more humid coast redwood forests, restoration of an anthropogenic fire regime may be unwarranted due to stand objectives and endangered species concerns. Given the historical importance of human ignitions in portions of this forest type, fire restoration is not a management goal in itself, but fire can be considered as a tool to achieve other management objectives, and be consistent with recent centuries of historical variability.

Steve Norman

|

|